All I Really Need to Know I Learned from the Dragon

what T1D has taught our family

Michelle MacPhee

D-Mom, M.S. (Psychology)

Wash your hands… Put things back where you found them (especially the BG meter)… (After a set change) clean up your own mess... When you go out into the world, watch for traffic, hold hands and stick together. These lessons are equally true for dragon tamers as they were for Robert Fulghum when he wrote All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten. This got me thinking about the lessons I have learned - not in kindergarten, but by living with diabetes dragon for the past fourteen years.

After our son was diagnosed at just over a year old, I went through my own process of emotional healing, separate from my son’s physical and emotional journey. I needed to create some meaning from my sadness, and find some universal truth that applied not just to diabetes, but to life.

Here are some of the things that the diabetes dragon has taught me about life so far.

If you want, you can take a short detour to read our family's diagnosis story:

It's Okay To Cry

To heal I needed to let myself grieve, I needed to be honest with myself about my feelings. Up to that point in our family's story, my approach to emotional coping with diabetes focused on the “it could be worse” side of things… It could be worse: he could have an untreatable disease. It could be worse: I could have lost a child in a car accident, or by drowning. It could be worse: we could all be starving in a developing country. It could be worse: we could be refugees from civil war.

This is an important coping strategy at the right time. Because it could, indeed, be worse. My son is still here. He can still live a healthy, happy life, full of all the things that he would have done if he had never been diagnosed with T1D, it will just take more thought and preparation.

But it could also be better. Diabetes is unfair, and it changes things. We lost the life we had, we have had to re-envision the hopes and dreams we had before diagnosis. And what I had not really allowed myself to experience was the “diabetes really sucks” side of things. I had been so busy convincing myself that all would be okay, I hadn’t acknowledged all that we had lost: the carefree naps of an infant; the freedom to let him eat nothing at all if he wanted;

a sense of security in life; the illusion that I could protect my children from harm. We had lost a lot. My grief was valid.

When I learned to balance each of those mind-sets – “It could be worse” and “It could be better” – my whole outlook changed. I started to have energy and motivation to deal with what had to be done, because I wasn't using up all my energy in denial. I remember my exact turning point. After our trip to emerg with our daughter, when I was facing the prospect of having two toddlers with diabetes, I finally took the time to go to a Friends for Life Conference in Vancouver. There I heard Joe Solowiejczyk (Family Therapist, Diabetes Nurse Educator, and PWD) talk about the feeling of powerlessness that many parents feel when their child is diagnosed with diabetes: that idea that I couldn't protect my child from this dragon, that I would do anything to take it away, and would even gladly take it myself, but I COULDN'T. I was powerless to prevent it, powerless to make it go away. When I listened to Joe, it was the first time I even realized that was how I felt. Powerless. I didn’t have the control that I thought I had over our son’s health, and that made me realize that, in reality, I have minimal control in life in general.

Which brings me to the second thing that I really needed to know about life, and learned from diabetes…

I Can't Control Everything

We often think that the biggest stress comes from having big responsibilities. But that’s not actually the case. The biggest source of stress actually comes from having big responsibilities for something over which we have minimal control.

THE GREATEST STRESS COMES FROM BEING RESPONSIBLE FOR THINGS

OVER WHICH WE HAVE LITTLE OR NO CONTROL.

It seems like that definition of "stress" fits type 1 diabetes extremely well:

Big Responsibilities.

Diabetes is one of the few chronic illnesses in which the patient (or his parents) is responsible for the majority of his own care (especially the day-to-day management of blood sugars, insulin dosing, nutrition, exercise, blah, blah, blah...) Plus the potential mishaps are multiple and serious, from long term complications to sudden death. The responsibility is huge.

Little control.

As you know all too well, diabetes is an unpredictable illness. Despite our best efforts, there are many factors that affect blood sugar and impact our health (or our children’s health), and at best we have some control over only a few of them. (Ever tried to control the release of hormones? The precise effect of exercise on blood glucose? The cumulative effect of the carbs and fat from a buffet meal topped off with ice cream??? It’s a losing proposition.)

The take home lesson for me was to separate what I could control from what I couldn't control, and then focus my efforts on the things I could control. For example, I can’t control how my son’s body deals with food from one day to the next, but I can control what foods I put in the grocery cart, how healthy they are, how quickly they raise blood sugar. I can’t control how far his blood sugar drops after a swim class, but I can check blood sugar regularly after the class to catch any “excursions”, and I can encourage regular physical activity for both of my kids to help with fitness and insulin sensitivity. I can’t control the BG spike that comes out of nowhere after a meal and whomps! him on the butt, but I can learn about insulin dosing, I can track my son's blood sugars to look for patterns, I can adjust insulin when needed. I can seek out workshops and events. I can connect to the community. I can systematically let go of my need for control.

So it’s true that, as most things in life, I can’t control diabetes. It’s equally true that I don’t have to let diabetes control me...

Diabetes Doesn't Have to Control Us

During the writing of this article I spoke to a D-dad whose daughter had been diagnosed with diabetes just a few weeks before. He and his wife had a trip planned as a couple, and now they were questioning whether or not they should leave their newly diagnosed daughter to take the trip, or cancel it, staying home to tend to the dragon.

What would you do?

We have had to face similar situations as a family over the years. Big and small decisions about who will “win” today, us or the dragon?

Do we go to that family dinner, when we know there will be no carb counts, and we'll have to guess wildly, and his blood sugar will probably be soaring later, and it will take hours to get it back to range? Do we go on that family trip to visit relatives out-of-province, when we know it will involve tons of preparation and anxiety? Do we sign him up for soccer lessons, when

we know he'll have lows, and then highs when we overcompensate, and the whole thing will mess up his blood sugar? Do we stop for a donut on the way home from church, knowing we’ll struggle with insulin resistance the rest of the day?

Sometimes our answer is "no, not today”. On these days, the dragon wins.

But we try to make that extra effort more often than not. We choose to do the pre-planning, deal with the fall-out, do what we would have done as a family if diabetes was not part of the equation. Because ultimately, we don't want diabetes to control us. We don't want to let diabetes win by sitting at home, doing nothing, and feeling like victims.

There are no victims here, only choices.

(And in case you’re curious… the man and his wife went on their trip. And their daughter was fine! Humans: 1 point; Dragon: 0.)

It's Better Together

Many people reading this right now would agree that diabetes is a heavy burden. The self care demands are relentless: checking blood sugar, giving injections or inserting pump infusion sets, adjusting insulin, watching for lows, watching for highs, counting the carbs in what you eat, taking fat and protein into account, adjusting for exercise. Even when you're sick and most need to rest, at that exact time the demands are even higher! Sometimes it feels like the weight of the world on your shoulders.

But the only thing worse than carrying the weight of the world on your shoulders is carrying it alone.

We each need to find someone to share the burden with. For me, that person is my husband Dean. I couldn't be here today, I couldn't do my work in advocacy, I couldn’t take a day off, if he wasn't involved and capable of managing diabetes when I'm not around.

But I lucked out, because when I was dating I wasn’t exactly looking for a self-trained pancreas. If I had known then what I know now, I would have had very different criteria for a potential husband.

MY "E-HARMONY" PROFILE THEN:

Seeking handsome man to share adventures, travel the world, and to make my toes tingle when we kiss. Good father a plus.

MY "E-HARMONY" PROFILE NOW:

Seeking patient man to get up in the middle of the night to check blood sugar and/or to clean up vomit. Must be patient, cooperative, calm in an emergency, and not faint at the sight of blood. Good father a must. Tingling toes a bonus.

My, oh my, things have changed! I don't care so much anymore that he's handy with a table saw and hammer, just that he's handy with a CGM sensor inserter; it matters less that he brings me roses, and more that he brings home the d-supplies from the pharmacy.

My d-partner happens to be my spouse, but that’s not the only option by far. Your "partner" may be a good friend, a relative, your child's grandparent or aunt or uncle, your pastor, your next door neighbor, another d-parent... Whoever you turn to, in whatever degree, please turn to someone. We all need at least one person to shoulder the burden with us.

And to keep that partnership strong we need to...

Blame Diabetes, Not Each Other

When things are tough and it's a crappy diabetes day, it's easy for me to get upset at my husband for the things he didn't do. For forgetting to make sure our son checks his blood sugar right after school, for miscalculating the carbs in the chili, for buying stuff at the grocery store that doesn’t have a carb label, that’s hard to guesstimate.

But when I get upset, it's not really my husband I'm mad at. He's just being human, just like I am human MANY times a day.

What I'm really mad at is diabetes.

Mad that the carbs have to be counted, mad that the blood sugar has to be checked, mad that the outcome doesn’t match our input, mad that diabetes creates work and stress. So I need to direct my anger where it belongs: at DIABETES, not my d-partner.

In our house, the only time one can use the derogatory and attacking word “stupid” is to talk about the dragon. As in, when blood sugar is high and that delays the start of supper: "Stupid Diabetes!" Or when a dear friend went on a hike with her family, but had to wait at the bottom with her son because his blood sugar was too low to proceed: "Stupid Diabetes!" Or when an injection hurts. Or a teacher doesn’t want him in her class because she can’t stand the sight of blood. Or we are too tired or overwhelmed or defeated to do even the basics but we have to do them anyway. STUPID DIABETES!

We're not stupid. Diabetes is.

Most of the time, when I vent my frustration directly at the real source of my frustration -- the diabetes dragon -- it helps me to move on emotionally.

And while we’re on the topic of partnership… Beyond needing a person to share the burden with, we need community.

It Takes a Village

When Max was first diagnosed, I thought our family could (and should) do it on our own. And technically, we did. But we were worn out and too often going around in circles. We were chasing an elusive solution, reinventing the wheel that, unbeknownst to us, others in the diabetes community had already invented.

When we finally met other parents we could share stories, swap ideas. They had simple solutions to challenges with which we had been struggling. For example, when Max first went on an insulin pump, we knew from his diabetes health care team what the choices were in terms of infusion sets. But our son had trouble with skin reactions to the adhesive tape that held the sets in place, and to the plastic cannula that sits under the skin. At a CPaK meeting I met Danielle, my soon-to-be friend and co-founder of Waltzing the Dragon. As another diabetes-mom whose son had had the same problems with skin sensitivity, she was able to suggest the one infusion set that worked for him; we tried it, and haven't had a problem since then. Maybe I would have found that product on my own, but after how many months, and with what level of frustration? It's possible we never would have found it, and would have continued to struggle, or even abandon the pump altogether. But because of community, our problem was resolved.

What I learned through this experience was that I needed to intentionally build in a network of support. If you want to do the same, here are some suggestions for how to meet other people who are also dancing with the diabetes dragon:

- Volunteer for an organization with a diabetes mandate, such as I Challenge Diabetes, Diabetes Canada, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), the Alberta Diabetes Foundation, or here at Waltzing the Dragon.

- Join in on recreational activities for people with diabetes, such as I Challenge Diabetes, CPaK in Calgary, Connected in Motion).

- Attend a diabetes conference, talk, or workshop: Kids n Us in Alberta; Friends For Life in Florida; a guest speaker brought in by your local diabetes centre (such as the Diabetes Clinic at the Alberta Children’s Hospital); a meeting like CPaK or T1D Talks in Calgary. You may even be able to Skype-in or Tele-Conference if you don’t live close enough to the event to attend in person.

- Reach out online. Read, comment and ask questions on a chat or forum (Children with Diabetes, Beyond Type 1, Facebook groups such as Parents of Type 1 Diabetics - Canada, or any of a number of groups specific to a diabetes technology or brand, such as Dexcom, T-slim, Medtronic, Libre…)

- Subscribe to and join the conversation on a personal experience blog.

When support entered my life, everything changed. Now when diabetes beats me up, there's someone I can call and say "WTF?!", someone to listen to my frustrations. We share practical information and tips, but more than that, we share the experience of powerlessness and of doing our best.

What else has the diabetes dragon taught me about life?

Focus on What You Value

The reason that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to diabetes problems is that we value different things. So how do we decide what’s the right answer for us? We start by clarifying for ourselves what matters most to us.

Dark times often show us what matters most. Diabetes pushed me and my husband to examine our values as parents and as a family, and to ask ourselves: with all the things that we want for our children, what do we want most for them? A nice house? Time with friends? An active faith-life? A chance to give back? As few blood sugar swings as possible? Reduced risk of complications? Stability? Freedom?

The answers will differ between families, there's no universal right or wrong answers in terms of how you “do” diabetes.

For example, when Max goes to another child's birthday party and the birthday cake is served, his blood sugar isn't always at an ideal level. There are times I haven't been able to give him insulin in advance, and the cake comes out, with double icing, and his blood sugar is 15.9. In that moment I have a choice: I can tell him he needs to wait until his blood sugar comes down, or I can let him eat the cupcake, knowing it will quickly drive his blood sugar even higher. These are competing values: I want to protect his health, and I know repeated high blood sugar increases the risk of diabetes complications. I know that being diagnosed so young means we have years to fight to keep his body healthy,

because by the age of 50, he will have had diabetes for 49 years. That’s 49 years of risk. On the other hand, I want him to be a little boy, and to do the things that other kids his age get to do. I don't want diabetes to rob more of his control, his happiness, his enjoyment of life. And if he misses out on that cake, or even has to wait until all the other kids are done, he may feel ripped off and resent diabetes for that. So do I give him the cake or not?

What would you do?

Your answer depends on your values. Again, there's no right or wrong answer. In this particular situation, our family often chooses to let him have the birthday cake. Because getting him back into range quickly doesn't guarantee freedom from diabetes complications. And even if it did, we would rather that he grow up whole, well-adjusted, and at peace with the diabetes dragon he is forced to live with, rather than resentful and feeling like he’s always at the mercy of diabetes. If the price of being well-adjusted is high blood sugar, and possible complications in the future, then we're willing to pay it. And then we work extra hard the rest of the time to make sure that that compromise is the exception, not the rule, because protecting his long term health also matters to us. That’s the best decision for our family, based on the things that matter most to us. But the “best decision” for your family may be different, and it is different for many families I have met. We all need to respect each other’s right to choose what’s best for our own family.

What else has the diabetes dragon taught me about life?

Success = Effort + Persistence

I used to think that success meant I had “arrived”, that I had won, that I had conquered whatever challenge was before me such that it no longer impacted me. But in the face of diabetes, I found that I had to redefine success. I’m learning that until there’s a cure for type 1 diabetes, I cannot defeat the diabetes dragon, I can only tame it. Success isn’t a destination, it’s a process.

That is, success in terms of diabetes care is not about reaching some external criteria of “winning”. We're winning not because he has perfect blood sugars (he doesn't!) and not because we're “done” grieving (we’re not! Grief is an ongoing, non-linear process, that tends to loop back on itself.) Further, we're not winning because we make flawless decisions as his parents, or because we're perfect role models for how to balance diabetes and life (we don't; and we're certainly not!)

But as a family, we are winning. Because we get up every day and continue to tame the diabetes dragon; as Joe Solowiejczyk puts it, we "suit up and show up", and that's what really counts.

We are winning because we don't let diabetes define us as a family - it's not the first thing we mention in our resumé - it's there, and it affects us, but we focus more on each of our hobbies and passions – Lego, beading, Minecraft, coding, swimming, bike-riding, photography, movies, art. That’s who we are. We succeed - at diabetes and in life in general - by putting forth a good effort, and by persisting with that effort through all the ups and downs.

Speaking of ups and downs, I have learned from diabetes that success doesn't depend on the outcome...

Input vs. Outcome

Diabetes has pushed me to evaluate myself not on the outcome (over which I have relatively little control), but on my input (here I have LOTS of control).

Let me illustrate by sharing my beef about the hemoglobin A1C test...

As you may know, A1C measures the "stickiness" of your red blood cells, and gives an indication of average blood sugar over the past few months. A high A1C means a person has spent a fair amount of time with high blood sugar; a lower A1C means they have spent relatively less time above the target range. It’s an outcome measure – that is, it measures the end result of a number of factors, some of which we can control, and some of which we cannot.

Now, before you get the idea that I think A1C is a pointless measure... it’s not! It’s helpful feedback about how we are doing in terms of our goals for managing blood glucose and keeping BG in range as much as possible. It also has predictive value in terms of long-term diabetes complications: lower A1c levels can greatly decrease the risk of long term complications (such as nerve, kidney and eye damage)1. In short, A1C is an important assessment tool for managing diabetes, and one that we should have assessed regularly.

But it’s not the only assessment tool that we should take into account in order to define success. And it shouldn’t be used to slap on a label of “good diabetic” or “bad diabetic”, both because that judgment doesn’t change behaviour, and because the actual A1C number may not precisely reflect our actual day-to-day effort. We may do many things right: we may eat healthy foods, exercise every day, track blood glucose readings and make regular changes to insulin doses as needed. But if after doing all that, we get an A1C result that's higher than we expected, we feel like a failure. The problem lies in evaluating ourselves based on the outcome (over which we have some control, but not complete control) rather than on our own actions and behaviour (over which we have much more control).

THE PROBLEM LIES IN EVALUATING OURSELVES BASED ON THE OUTCOME

RATHER THAN ON THE INPUT (OUR ACTIONS).

If we base our feelings about ourselves and our kids (our feelings of success, pride and accomplishment) on the part of the process that is less under our control (outcome), while downplaying the part that IS under our control (our actions), then we’ll constantly be chasing an unattainable goal.

I've been there and done that!

There are times we felt like we did everything we could - we checked BG several times throughout the day, logged blood sugars, got regular exercise as a family, ate balanced, moderate glycemic meals, pre-bolused, adjusted insulin regularly and yet the A1C result came back higher than we expected.

Maybe Max went through a growth spurt, or had a cold that messed up his blood sugars for a few weeks.

Whatever the reason, we felt like all that effort was for nothing. The outcome wasn't what we hoped for, so we felt like we had failed.

We should instead look at our input, at the effort that we put in, and all the ways we contributed positively to the outcome. If our effort was good, then we should pat ourselves on the back, regardless of the outcome. We should count ourselves as winners because we did all that great stuff. And we have to remind ourselves that it could have been much higher if we hadn't done all the work!

(Of course, at times our recent effort wasn’t anything to be proud of. At those times, the A1C result is an opportunity to make a course correction, to change our input and make a better outcome more likely in the future. Still, no self-judgment required!)

Just as this concept applies to me as a parent, it also applies to my kids...

My kids are healthier and happier when they evaluate their efforts, not the outcome

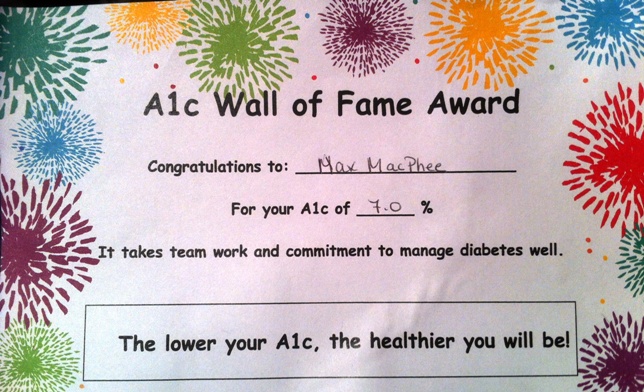

At the Alberta Children’s Hospital Diabetes Clinic they have this wonderful incentive program to motivate kids to keep their A1C lower. The first time the test result is under 7.5 for two consecutive tests, the child gets a gift card for Toys R Us, or iTunes, or something valuable to them. Great program, and one that I fully believe works to motivate kids. But one pitfall is that for younger kids like my son, the A1C is more a measure of MY actions than of his. As his parents we count the carbs, adjust his insulin doses, decide what foods are being served and how healthy they are (or not); he just shows up, delivers insulin and eats.

So a few years ago, for the first time ever, our son's A1C result was under 7.5. The discussion began that if it stayed under 7.5 for the next visit, he would get a Toys R Us card. He immediately began to spend it in his mind: “Do I want the Fire Chima Lego set or one from the Lego Movie?” Oh the possibilities!

I began to worry. School would be starting during that time period, which always creates a few weeks of instability with his numbers. And what if he had too many summer popsicles without enough of a pre-bolus, or too many ice cream cones (the fat in them leads to insulin resistance and high numbers later)? What if we didn't stay on top of his insulin and didn't do our job well enough as parents? Then again, what if we worked hard but he didn’t, so he learned that gift cards fall from the sky without any effort on his part? We want him to learn that his actions have consequences, and he's in charge of his own future... how will he learn that if he gets a reward he didn't truly earn?

It was important to us to have some aspect of this A1C goal that was under his control. So we thought of the ways that he could impact his own health, even at his young age (he had just turned 7). One area that had always been a sticking point was waiting to eat after he had given himself insulin. Since insulin works so much slower than food does, it's wise to use a pre-bolus - that is, give insulin, then wait about 15 minutes before eating, to give that insulin a head start. Max had always argued about having to wait those 15 minutes. Especially for those summer popsicles and other treats. Waiting's hard when you're a kid! But this was one way he could participate in protecting his own health - he could consistently wait before eating. And we explained to him why this was a good idea, gave him control of the timer - he would deliver insulin through his pump, set the timer for 15 minutes, and then eat only once the timer went off. He did still grump about it sometimes, but he did a great job of doing his part, we were really proud of him.

When the next A1C test approached, we started to think: What if the result isn't below 7.5? He'd had some pretty wild swings over the previous few weeks. Here he's done all this work, we don't want him to get the wrong message, that working hard doesn't make a difference. So we decided that, whatever his A1C result was, we would make sure he got his Toys R Us gift card, even if it came from us instead of from the clinic. Because he had done what was asked of him and done it well (his input was great), regardless of how his A1C would turn out (the outcome). So what happened?

Happy ending for everyone!

This revelation around input versus outcome was a powerful one for us. And it lead me to another diabetes life lesson... If making an effort and changing his own behaviour is a positive thing that teaches my son about cause-effect and makes him feel empowered, then why was I still doing almost everything for him??? Max was diagnosed at the age of 14 months. Of course we, as his parents, did everything in terms of diabetes care – he was only a baby! But as he grew, and as I looked at the non-diabetes tasks that I was also doing for his sister, I realized...

If I do it all for them, they will expect me to do it all for them!

I realized somewhere along the way that it's important to hand off diabetes care to my son. One day I will not be there on a minute-to-minute basis, and all I have learned will fade away if I don’t hand over these diabetes skills to him. Not at the last minute when I realize “holy crap! He’s moving away in a week and he doesn’t know how to change an infusion set!” or “Oh no! He turns 18 in two days and I won’t be able to attend his doctor’s visits unless he invites me!” No, I would like to give our whole family as much time as possible to adjust as his support system changes and we are no longer in the driver’s seat.

I would like to hand over the baton piece by piece and skill by skill, not an all-or-nothing skill dump where one day I do it all and the next day he has to do it all.

With planning and research, I can make the transition age-appropriate, systematic and manageable. I can avoid the perils of giving adult responsibilities to him when he’s a kid. I can check in and see how he’s coping with the new responsibilities, and not to assume he’s ok with heavy responsibilities just because from the outside he looks like he’s handling it.

I need to remind myself that, as a parent, it's not MY diabetes, it’s his. And as much as I don’t want to think about that future day now, I know that eventually Max will have to manage HIS diabetes largely on his own, with our support.

A few years back, I felt overwhelmed by that idea. I didn't even know where to start! So I sat down and wrote a list of all the things we do to manage Max's diabetes.

I picked a few of these, and broke apart the skill into steps. I thought about each step and assessed whether he:

- 1. currently does that step on his own, or

- 2. is capable of learning that step, but for whatever reason we still do it for him (these are good tasks to consider handing over), or

- 3. could not and should not yet do that step on his own (he’s not ready developmentally, physically, mentally or emotionally)

This process helped me figure out what tasks, or parts of tasks, he could learn to do more independently, without overwhelming or burdening him (or me!).

For example, when we looked more closely at these tasks as a family, we discovered that Max was capable of, and actually wanted to change the lancet in the lancing device he uses for BG checks. For some reason, he finds this part very cool, and actually asked me if he could start doing it. So just like the preschooler who wants to help with dusting, I let him "dust", metaphorically speaking, because if I take a cue from his current motivation, then I don't have to convince him later when he no longer thinks it's so cool. Other examples? He now makes his own snacks and lunch for school (with our supervision on the nutrition end!) and we calculate the carbs together; he writes his own carb list based on our joint efforts. Also, over the past several months Max has learned to program in a Combo bolus on his pump (we’re still responsible for giving him the numbers to program in – how to arrive at those numbers is a clear NOT YET).

But let’s be flexible…

It’s important to point out that just because we hand things over, doesn't mean we can't take them back (for a moment, for a day, for a week, for an indefinite period of time) if we see our child struggling with the weight of the responsibilities. That could be as simple as calculating meal insulin for your teen (even though they’re capable of doing so and usually do it), or dialing the pen and giving the injection to your older elementary age child; or it could be more involved, like looking over the logbook and helping adjust insulin doses to prevent a pattern of lows that your young adult has been having lately.

Even if they're 42.

I'm a grown adult, but when I'm sick, it's nice to be taken care of. It's nice if someone makes me tea and brings it to me in bed. How much more is this true for diabetes? When you're sick and run down, the demands of diabetes are that much more demanding. So if I can lift that burden for my son temporarily, even when he is a grown adult, then I want to do that for him, out of love. And just like when I get over a cold I start making my own tea again, I trust that when he gets over his “cold”, he'll pick his diabetes care back up again.

In the face of all this talk about burdens and demands, it’s easy to lose perspective. Sometimes I need to remind myself to...

Count My Blessings & Pay It Forward

As much as living with a chronic illness like diabetes is rough at times, I also need to recognize how fortunate our family is to live where we do, with the support of numerous diabetes organizations and with access to the excellent health care and treatment options that we do. I have discovered that sharing my time, skills, and financial resources with others, here at home and outside of Canada, has been a source of hope and healing for me.

Financial support

In developing countries, getting basic diabetes supplies like insulin and syringes can be a very real obstacle for families affected by diabetes; a bottle of insulin can cost as much as the average person earns in a month, so parents in these countries may have to make heart-breaking decisions between treating their child's diabetes, or feeding the rest of the family. I thank God that's a decision I've never had to make. I've heard about a pair of brothers, both diagnosed with diabetes, who had to share one syringe for a year! Something as simple as storing insulin a cool, dry place can be a challenge…

There are organizations like Life for a Child who are doing something about these issues. Their vision is that no child should die of diabetes. (Can you believe that’s even necessary? In 2018??!! And yet it is.)

By partnering with diabetes centers in lower-income countries to provide young people with insulin and syringes, blood glucose monitoring equipment and test strips, clinical care, HbA1c testing, diabetes education, workshops, camps, resources, and support for health professionals, Life for a Child gives these children access to the basic diabetes care that is a given here in Canada.

One organization that LFAC supports is Dream Trust, a registered charitable organization in Nagpur, India, whose goals include “ensuring survival of diabetic children… reducing the long term chronic complications… and creating better awareness & education of children and their parents.” A partnership between Dream Trust and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario’s (CHEO) Division of Endocrinology in Ottawa gives us a point of contact here in Canada, and allows Canadians to receive a tax receipt for contributions made in support of Dream Trust.

Waltzing the Dragon supports Dream Trust through CHEO, paying it forward by donating 5% of our gross income to the program. We invite you consider supporting Life for a Child or a similar organization from wherever you are in the world, so that other kids with diabetes have a chance at life and health.

Giving my time

Lots of people of all ages and backgrounds have shared a ton of time and talent with our family in order to make our life with the diabetes dragon a little smoother. Gratitude for that was a large part of the reason that Danielle and I started Waltzing the Dragon several years ago.

If you have even a few hours to share, with a desire to build community, to help and be helped, then consider donating some time to a diabetes-related organization. I would LOVE some help with Waltzing the Dragon, for one. Producing this online resource involves writing, web design, analytics support, marketing, networking, clinical knowledge and experience, real-life knowledge and experience, photography, cooking and baking, tech savvy, social media savvy... the list goes on. If you have a skill to share, or simply want to get involved, I would love to hear from you.

And finally, there’s one more thing that diabetes has taught me. In the midst of all the demands and drudgery and worries, there needs to be some time for joy, for fun, for time well-wasted. So…

Whenever Possible... Dance!

I would love to hear your family's diabetes story and the lessons you've learned... you can send me an email, or post to Waltzing the Dragon's Facebook page to share your thoughts.

References:

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993 Sep 30;329(14):977-86.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE