Effective Support for Students with T1D: An Overview

Michelle MacPhee

D-Mom, M.S. (Psychology)

So your child or teen was recently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and now it’s time for her to go back to school. Or your child was diagnosed months or years ago and is now about to start their school career. Or maybe you and your child have been managing diabetes within the school system for some time, and you want to make sure you’ve covered all the bases. Whatever your individual situation, there are some common themes and processes which may help take the fire out of the diabetes dragon at school.

It is important to note that how you fold diabetes care into your child’s school experience will vary depending on your child’s age and ability to complete diabetes self-care tasks; younger children (particularly those in Kindergarten to grade 3, or beyond) will likely require more direct support than older children. But the need for support doesn't go away as a child transitions through elementary school to junior high/middle school, and then to high school - it just requires a shift in perspective. The challenges shift, support looks different as a student grows.

Planning Ahead

To begin with, if you have more than one prospective school in mind, it is wise to meet with each school’s principal well in advance of the start of school year, to get a sense of how well a school’s philosophy and resources will match your family’s needs and values.

- Are they open to working with you to manage your child’s diabetes at school?

- Is there a culture of flexibility and supporting each other, or is it “everyone for themselves” and “a rule is a rule”?

- Do they have other children with medical needs? Other students with type 1 diabetes?

- Do they have a school nurse*, and if so, how much time does he/she spend on-site?

- Do they have any teaching assistants specially trained to support students with medical needs?

I thought the charter school at the end of our street, with an academic program I respected, was a logical choice – until the principal flatly informed me that the school would not be able to meet my son’s medical needs in any way. Clearly, this is a human rights violation, and I could have fought for my son’s right to attend that school. However, our primary goal was to find a school that would be willing to partner with us, not one we would have to fight. So with that in mind, it was good to know early on that the school was not a good fit for our family. We were free to find a school that was.

Tip from the Trenches

*In our experience, most school nurses in Calgary are present for less than one day per week; their role is not to support individual students on a daily basis, but to oversee public health issues such as vaccinations, nutrition, and dealing with illness outbreaks. They can, however, be a valuable resource for medical information and support to school staff in implementing plans at school.

-Michelle

Appreciating Each Other

Of course, if you don't want to "school shop," if your child is already enrolled at a given school, or if you chose a certain school for reasons that have nothing to do with diabetes (putting the dragon in its place is a healthy parenting move, imo!) there are a number of factors within your control which may make it more likely that your family’s experience at a given school is a positive one.

One of these factors is your participation in information-sharing events at school. If your child is new to a school or entering kindergarten, many schools offer an orientation evening. This is an excellent opportunity to meet prospective teachers and administrators, and to get a preliminary impression of what resources are available at the school, as well as what challenges may need to be resolved. At our son’s school orientation, we also met the school nurse, which meant that she could be involved from the beginning in meetings to develop our son’s diabetes care plan.

These initial tours and meetings are an opportunity to exercise perhaps the most important factor under your control – your role in setting up a positive partnership with your child’s new school, based on mutual respect and cooperation. Everyone – especially your child with diabetes – will benefit from cooperative (rather than adversarial) interactions between home and school. Try to put yourself in the place of your child’s principal and teachers: they are very busy, their time is in high demand; they have what might as well be a million responsibilities, to sometimes hundreds of other students, many of whom also have special needs, be they medical, developmental, social, behavioural, or educational. The vast majority of teachers and administrators are doing their best to care for the children in their care, and doing a great job at that. If you approach them with appreciation for all of this in mind, they will be more likely to bear in mind all of your demands and pressures as parent, more likely to recognize that you also have a million responsibilities (to your other children, your spouse, your work, to yourself – preserving your sanity and well-being), and more likely to respond with the support that is critical to keep your child safe under their care. Together you can work toward win-win solutions that work for everyone, especially for your child.

(I enjoyed the mirror images of “A Message to School Staff” and “A Message to Parents” in the JDRF International “School Advisory Toolkit for Families” – for information on how to obtain your copy, see Other Resources for School and Diabetes.)

I acknowledge that not everyone’s interaction with their child’s school has been positive. I’ve spoken with and read articles about parents who I sincerely believe have approached school staff with respect and a willingness to cooperate, but have not received a response in kind. My plea for an atmosphere of cooperation is directly equally at school staff; positive interactions require that both parties make an effort. However, the fact still remains that, although you’re not guaranteed a positive outcome, you are much more likely to generate one if you assume from the outset that everyone will be able to work together, only changing your approach if you have clear evidence that this approach is not resulting in a school setting for your child that promotes his health, safety and learning. It is also important to bear in mind that, unlike our American neighbours (who have 504 Plans and the Americans with Disabilities Act) Canada does not have clear federal legislation to ensure that schools support our children with blood glucose monitoring and insulin administration.* Since Education is a provincial matter, policies and practices vary from province to province. As a result, we have to rely more on working together – and that starts with the only person you can control: yourself.

Tip from the Trenches

We try to phrase things positively, in person and in our written plans. We request or suggest rather than dictate or demand. We call the core group of staff and our family “The Team”. We refer to staff as the “school setting experts”, while we are experts about our child and his diabetes. When we encounter problematic situations, we choose to see them as “challenges”; then we ask ourselves how we can come together to make this work, to find win-win solutions; we ask school staff, “How can we address this?” so as not to become adversarial.

– Parent of a Grade 3 child with diabetes

Meeting with School Staff

Before school starts (or as soon after diagnosis as possible during the school year), it’s a good idea to call the school to schedule a meeting with the principal, teacher(s), and any other key school staff (such as the school nurse, or classroom assistant, if applicable. Don’t overlook the value of the administrative assistant/secretary; in many schools they are the eyes and ears of the school, are most aware of day-to-day activities such as class schedules, teacher schedules, and substitute teachers.). Ideally, this meeting would last 30-60 minutes and occur before the start of the school year (or before your child returns to school after a mid-year diagnosis).

At this meeting, you should be prepared to talk about what diabetes is, what that looks like for your child, and what you anticipate your child’s needs may be. If your child is newly diagnosed, you may not even know yet what his needs will be. That’s okay. Just share what you know (your child’s diabetes health team may help you anticipate possible needs and challenges), and be prepared for ongoing communication with school staff so that you can tweak the process over time. If your child is new to the school, you may want to ask questions about current school routines, and discuss how your child’s needs may be met within those existing routines, as well as where accommodations may be helpful.

Tips for the Initial Meeting:

What Do School Staff Need to Know about My Child?

In terms of specific information to share at this meeting, it helps to provide the principal with the information that will form the basis of your child’s Diabetes Care Plan, a document which outlines your child’s individual needs and what specific actions are necessary to meet those needs. A Diabetes Care Plan (or “Medical Care Plan”, or simply “Care Plan”) provides guidelines to school staff to increase your child’s safety and health during her time at school. It may include identifying/emergency information, details about how your child experiences lows and what to do about it, information about how snacks/meals and illness should be handled, and guidelines for physical activity.

See Writing a Diabetes Care Plan for a more detailed description of care plans, as well as for examples of blank templates and completed care plans.

At this time, you may also discuss procedures for communication. Maybe daily emails or texts between home and school will work best. Some schools use journals or communication books which travel back and forth between school and home. If your child’s school does not have such a system in place, you may want to suggest starting one for your child. Some teachers write the blood glucose check results on a sticky note each day (along with action taken), and stick that note on the child’s agenda.

Another important discussion involves where emergency low treatments/snacks will be stored around the school. Identify key locations in the school where your child will spend his time and discuss how and where to stash fast-acting carbs – his classroom, the gym, the music room, the lunch room, the bathroom, the bus, the main office. Create packages of fast-acting carbs, clearly labelled with the amount of carbs, your child’s name and his class number, and your contact information (if you are comfortable with that information being publicly available). Then make sure someone (probably you, the parent) actually goes around the school and installs them.

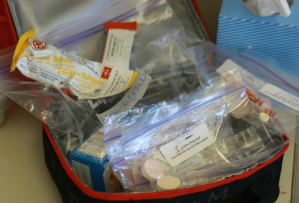

It is also essential to create a portable low kit for your child to take with her anytime she leaves the classroom (outside at recess, gym class, library visits, music class, assemblies, fire drills, lock downs. For convenience, it may be carried in an athletic or pump pouch, purse/bag, lunch kit, or in his pocket, whatever works best for your child. For younger children, it may be best if the teacher is responsible for taking this portable kit wherever the class goes (unless it is the type that your child wears all the time, like a fanny pack). This portable low kit should contain, at a minimum, a few doses of low treatment and a blood glucose monitor/test strips.

However, it would also be wise to have a larger store of snacks and fast-acting glucose available at the school, both for day-to-day use, and also for those exceptional circumstances where a significant amount of carbs may be needed. We heard from one teacher who had a student with type 1 diabetes in her class when the school experienced a lock down – they needed to have access to enough snacks to last several hours. Plan for the worst and hope for the best – although it is not likely to happen, you can relax knowing you’re fully prepared.

This initial meeting is also a good opportunity to share your goals and priorities for your child’s school experience, as they relate to diabetes-related plans. For us, it’s important that our son has a school experience that is as typical as possible, so many of the solutions we discussed revolved around that goal. For other parents, avoiding lows may supersede everything else. For teens, social acceptance and fitting in may guide the specific plans constructed. Our son is fairly shy and quiet, so our main focus for him in kindergarten is social interaction. This will guide our diabetes plan decisions, such as how much to involve classmates in supporting his diabetes care. For all students with diabetes, frequent blood glucose checks and/or correcting highs are an important part of your school action plan, to increase the probability of blood glucose staying in target so your child is able to feel his best and fully engage in school.

At this time, you may also discuss procedures for communication. Many schools use journals or communication books which travel back and forth between school and home. If your child’s school does not have such a system in place, you may want to suggest starting one for your child. Or perhaps daily emails or texts between home and school would be useful. Some teachers write the blood glucose check results on a sticky note each day (along with action taken), and stick that note on the child’s agenda.

There are also a number of valuable wireless options for sharing your child’s blood glucose results between home and school. Most blood glucose meter companies have an app to share the blood glucose results electronically. NightScout (CGM in the Cloud) allows you to share data from many CGM and flash monitoring systems. And for those using CGM, Decxom G5 Mobile app (with Share) does the same. (Medtronic also has a remote data-sharing app on the way for its 630G, pending approval from Health Canada.) Depending on the system, you can receive notifications about blood sugar (via email or text), alerts for out-of-range readings, even CGM trace data, allowing you to stay in touch with your child’s health even while they are away from you at school.

Plan for Lows

Another important discussion involves where emergency low treatments/snacks will be stored around the school. Identify key locations in the school where your child will spend his time and discuss how and where to stash fast-acting carbs – his classroom, the gym, the music room, the lunch room, the bathroom, the bus, the main office. Create packages of fast-acting carbs, clearly labelled with the amount of carbs, your child’s name and his class number, and your contact information (if you are comfortable with that information being publicly available). Then make sure someone (probably you, the parent) actually goes around the school and installs them.

Many families create a portable low kit for their child to take anytime she leaves the classroom (outside at recess, gym class, library visits, music class, assemblies, fire drills, lock downs). For convenience, it may be carried in an athletic or pump pouch, purse/bag, lunch kit, or in his pocket, whatever works best for your child. For younger children, it may be best if the teacher is responsible for taking this portable kit wherever the class goes (unless it is the type that your child wears all the time, like a fanny pack). This portable low kit should contain, at a minimum, a few doses of low treatment and a blood glucose monitor/test strips.

It would also be wise to have a larger store of snacks and fast-acting glucose available at the school, both for day-to-day use, and also for those exceptional circumstances where a significant amount of carbs may be needed. We heard from one teacher who had a student with type 1 diabetes in her class when the school experienced a lock down – they needed to have access to enough snacks to last several hours. Always plan for the worst case scenario – although it is not likely to happen, you can relax knowing you’re fully prepared.

What Matters Most to You?

This initial meeting is also a good opportunity to share your goals and priorities for your child’s school experience, as they relate to diabetes-related plans. For us, it’s important that our son has a school experience that is as typical as possible, so many of the solutions we discussed revolved around that goal. For other parents, avoiding lows may supersede everything else. For teens, social acceptance and fitting in may guide the specific plans constructed. Our son is fairly shy and quiet, so our main focus for him in kindergarten is social interaction. This will guide our diabetes plan decisions, such as how much to involve classmates in supporting his diabetes care. For all students with diabetes, frequent blood glucose checks and/or correcting highs are an important part of your school action plan, to increase the probability of blood glucose staying in target so your child is able to feel his best and fully engage in school.

Tip from the Trenches

On the flip side, to avoid teachers viewing my daughter as a diabetic rather than a child with diabetes, I try to keep separate the conversations about diabetes and those about other school goals. For example, I don’t discuss diabetes during parent-teacher interviews, as we are there to talk about my daughter and her education, not her diabetes.

~Lori, mom of a Grade 6 girl with diabetes

Finally, it’s nice to take the time to express your appreciation for the efforts of your child’s teachers and administrators. An email following your meeting thanking them for their time, or a Christmas/holiday card, go a long way to helping school staff realize their efforts make a difference for your family. Some families choose to show their appreciation by bringing a light snack to meetings, such as home-made cookies or a box of Timbits. Any genuine expression of your appreciation would be welcome by school staff.

The above information was reviewed for content accuracy by clinical staff of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Diabetes Clinic.